종교다원주의와 기독교인의 자기이해

세계교회협의회

Religious Plurality and Christian Self-Understanding

World Council of Churches

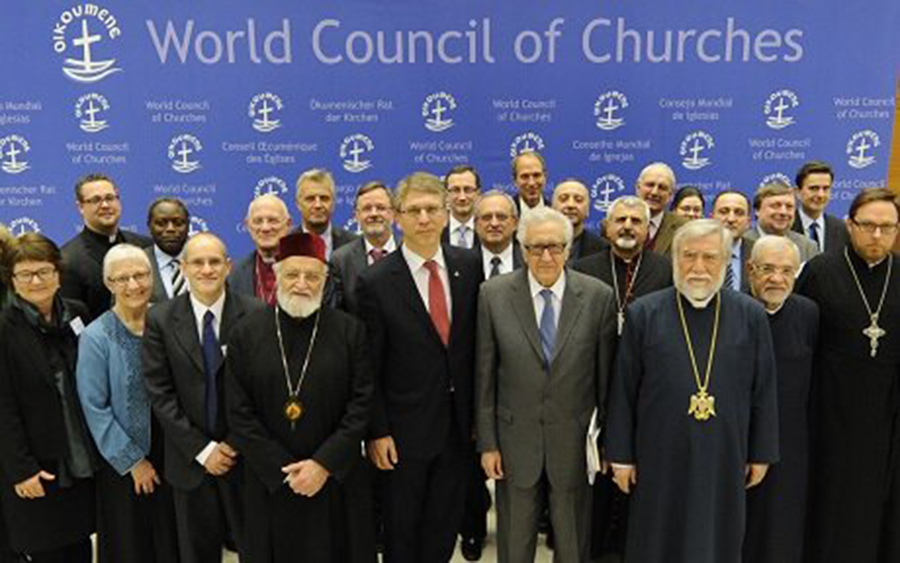

[소개문] 이 문서는 2002년 WCC 중앙위원회가 신앙과 직제, 종교 간의 대화국, 선교와 전도에 관한 세 팀과 이들 주제에 대한 각 위원회 또는 자문 기구가 연구한 결과이다. 종교다원주의에 대한 신학적 접근 문제는 WCC의 의제에 여러 번 제기되어 1989년(샌안토니오 세계선교전도대회, 역자 주)과 1990년(바아르선언문, 역자 주)에 일정한 합의에 도달했다.1 최근 몇 년 동안 이 어렵고 논쟁적인 문제를 재검토할 필요가 생겼다. 서로 다른 콘텍스트와 교파들 그리고 종교학, 선교학, 조직신학에 정통할뿐 아니라 이 세 분야의 네트워크에 연결된 20여 명의 학자들이 2년 동안 이를 연구하는 상당한 노력을 기울였다.

이 글은 WCC의 견해를 전적으로 대변하지 않는다. 위원회의 논의는 이 주제가 얼마나 중요한지, 뿐만 아니라 얼마나 논란의 여지가 있는지를 보여주기에 세심한 신학적 작업이 필요하다. 이 문서는 토론과 토론을 위한 배경 문서로 공유된다. 집회 참가자나 교회 및 기타 파트너의 추가 의견, 비판적 제안을 환영한다. 제안은 종교다원주의 세상에 살고 있는 기독교인의 자기 이해와 증거의 핵심 문제에 대한 지속적인 성찰에 반영될 것이다.2

종교다원주의와 기독교인의 자기이해

세계교회협의회

서문

“땅과 그 안에 있는 모든 것과 세계와 거기에 거하는 자가 다 여호와의 것이로다”(시 24:1). “해 돋는 데부터 해 지는 데까지 내 이름이 만국 중에 크며 각처에서 내 이름을 위하여 분향하며 정결한 제물을 드리며 내 이름이 열국 중에 크도다. 만군의 여호와의 말이니라”(말 1:11). “그때 베드로가 그들에게 말하기 시작했다. "하나님은 사람을 외모로 취하지 아니하시고 각 나라 중 하나님을 경외하며 의를 행하는 사람은 다 받으시는 줄을 내가 참으로 아노라"(행 10:34-35).

1. 시편 기자, 선지자, 베드로의 경험은 오늘날 우리에게 무엇을 의미하는가? 예수 그리스도에 대한 우리의 믿음을 기쁨으로 확증하면서도 세상에서 하나님의 임재와 활동을 분별하려 한다는 것은 무엇을 의미하는가? 우리는 종교다원주의 세상에서 그러한 확언을 어떻게 이해하는가?

I. 종교다원주의의 도전

2. 오늘날 세계 거의 모든 지역의 기독교인들은 종교다원주의 사회에 살고 있다. 다원성과 그것이 일상생활에 미치는 영향은 타 종교 전통들의 사람들을 이해하고 관계를 맺는 새롭고 적절한 방법 모색을 요청한다. 종교적 극단주의와 전투적 태세의 부상은 종교 상호 관계의 중요성을 부각시킨다. 종교적 정체성, 충성심, 감성은 너무나 많은 국제 및 인종 간 갈등의 중요한 구성 요소가 되어 20세기에 결정적인 역할을 했다. 누군가 "이데올로기의 정치"가 우리 시대에 "정체성의 정치"로 대체되었다고 말했다.

3. 모든 종교 공동체는 새로운 만남과 관계로 재편되고 있다. 정치, 경제, 심지어 종교 생활의 세계화는 지리적으로나 사회적으로 고립된 지역 사회에 새로운 압력을 가한다. 인간 생활의 상호 의존성과 세계의 긴급한 문제를 다루는 데 있어 종교적 장벽을 넘어 협력해야 할 필요성에 대한 더 큰 자각이 생겼다. 그러므로 모든 종교들은 상호 존중과 평화 속에서 살아야 하는 글로벌 공동체의 출현에 기여해야 한다는 도전을 받고 있다. 분열된 세상에 정의, 평화, 치유를 가져올 수 있는 힘인 종교의 신뢰성이 위험에 처했다.

4. 그러나 대부분의 종교는 정치권력과 특권과 타협하고 폭력에 가담하여 인류의 역사를 훼손한 고유한 역사를 가지고 있다. 예를 들어 기독교는 한편으로 모든 사람에 대한 하나님의 무조건적인 사랑과 수용의 메시지를 가져온 힘이었다. 다른 한편으로, 슬프게도 그 역사는 박해, 십자군, 원주민 문화에 대한 무감각, 제국주의 및 식민주의 계획과의 공모와 책략과 결탁으로 점철되었다. 사실, 그러한 권력과 특권에 대한 모호함과 타협은 모든 종교들의 역사의 일부분로, 우리의 종교에 대한 낭만적인 태도를 경고한다. 더욱이 대부분의 종교는 고통스러운 분열과 분쟁이 수반되는 엄청난 내부 분열의 다양성을 보여준다.

5. 오늘날 이러한 내부 분열, 분쟁은 종교 간의 상호 이해와 평화 증진의 필요성의 관점에서 보아야 한다. 공동체의 양극화의 증가, 공포 분위기의 팽배, 우리의 세상을 휩쓸고 있는 폭력 문화를 감안할 때, 분열된 인간 공동체를 치유하고 온전함을 가져다주려는 사명은 우리 시대의 종교가 직면한 가장 큰 도전이다.

기독교 신앙의 변화하는 콘텍스트

6. 세계 종교 상황은 유동적이다. 서구 세계의 일부 지역에서는 제도로 표현된 기독교 곧 교회가 쇠퇴하고 있다. 새로운 형태의 종교적 헌신은 사람들이 점점 더 개인의 믿음과 제도적 소속감을 분리함에 따라 등장한다. 세속적 생활 방식의 맥락에서 진정한 영성 찾기는 교회에 새로운 도전을 제시한다. 더욱이, 힌두교인, 이슬람교인, 불교도, 시크교도 등과 같은 다른 전통을 가진 사람들이 소수자로서 점점 더 이 지역으로 이동하는 바, 다수의 공동체와 대화해야 할 필요성을 종종 느낀다. 이러한 상황은 그리스도인들이 자신과 이웃 모두에게 의미 있는 방식으로 신앙을 표현할 수 있도록 도전한다. 대화는 믿음의 헌신과 말과 행동으로 표현하는 능력을 전제로 하기 때문이다.

7. 복음주의와 오순절주의 기독교는 세계의 일부 지역에서 빠르게 성장하고 있다. 다른 일부 지역에서는 기독교인들이 새롭고 활기찬 형태의 교회 생활을 수용하고 토착 문화와 새로운 관계를 맺음에 따라 급격한 변화를 겪고 있다. 기독교가 세계의 일부 지역에서는 쇠퇴하는 것처럼 보이지만 다른 지역에서는 역동적인 세력이다.

8. 이러한 변화는 우리가 타 종교 공동체와의 관계에 전보다 더 주의를 기울일 것을 요구한다. 그들은 우리에게 차이점을 가진 "타인"을 인정하고, 그들의 "이상함"이 때때로 우리를 위협하더라도 낯선 사람을 환영하고, 스스로를 우리의 적으로 선언한 사람들과도 화해를 추구하도록 도전한다. 다시 말하자면, 우리는 세상의 종교들 사이의 창의적이고 긍정적인 관계에 기여하는 영적 분위기와 신학적 접근 방식을 개발해야 하는 도전을 받고 있다.

9. 종교들 간의 문화적, 교리적 차이는 종교 간 대화를 항상 어렵게 만든다. 이것은 국제적인 갈등과 상호 의심과 두려움으로 말미암아 발생하는 긴장과 적대감 때문에 점점 악화되고 있다. 더욱이 기독교인들이 선교의 새로운 도구로 대화를 선택했다는 인상과 '개종'과 '종교의 자유'에 대한 논란이 완화되지 않고 있다. 따라서 종교적 분열을 초월하는 대화, 화해, 평화 구축은 시급한 과제가 되었지만 결코 고립된 사건이나 프로그램으로 해결되지 않는다. 여기에는 믿음, 용기, 희망이 지속되는 장기간의 어려운 과정이 수반된다.

질문의 목회적 차원과 신앙적 차원

10. 기독교인들이 종교다원주의 세상에서 살 수 있도록 준비시켜야 하는 목회적 필요가 있다. 많은 기독교인들은 자신의 믿음에 전념할 수 있는 방법을 찾고 있지만 아직 다른 사람들에게는 열려 있지 않다. 어떤 사람들은 기독교 신앙과 기도 생활을 심화시키기 위해 다른 종교 전통의 영적 훈련을 사용한다. 또 다른 사람들은 다른 종교 전통에서 추가적인 영적 고향을 찾고 "이중 소속"(double belonging)의 가능성에 대해 말한다. 많은 기독교인들은 타 종교인 간의 결혼, 타 종교를 가진 사람들과 함께 기도하라는 부름, 호전성과 극단주의에 대처할 필요성을 다루기 위한 지침을 요청한다. 다른 사람들은 정의와 평화 문제에 관해 다른 종교 전통의 이웃들과 함께 일하면서 인도를 구한다. 종교다원주의와 그 함의는 이제 우리의 일상생활에 영향을 미친다.

11. 기독교인으로서 우리는 타 종교 전통과의 새로운 관계를 구축하려고 노력한다. 왜냐하면 복음 메시지에 본질적이고, 세상을 치유하는 하나님과의 동역자로서의 사명이 그것이 내재되어 있다고 믿기 때문이다. 그러므로 하나님의 모든 백성에 대한 하나님의 관계의 신비와, 사람들이 이 신비에 반응하는 다양한 방식은 우리로 하여금 종교다원주의 세계에서 타 종교의 실재와 그리스도인으로서 우리 자신의 정체성을 더욱 완전히 탐구하도록 초대한다.

Ⅱ. 영적 여행으로서의 종교들

기독교 여행

12. 흔히 종교를 "영적 여행"이라고 말한다. 기독교의 영적 여정은 하나의 종교 전통을 풍요롭게 하고 날카롭게 형성했다. 초기에 주로 유대인-헬레니즘 문화에서 태동했다. 기독교인은 "낯선 사람"(나그네) 경험을 했고 지배적인 종교 및 문화 세력의 한 가운데에서 자신을 정의하기 위해 고군분투하는 박해받는 소수자 경험을 했다. 그리고 기독교는 세계 종교로 성장함에 따라 내부적으로 다양해지고 접촉하게 된 많은 문화에 의해 변형되기도 했다.

13. 동방 정교회는 역사적으로 문화 참여와 구분이라는 복잡한 과정에 연루되어 왔으며, 수세기에 걸쳐 선별된 문화적 측면의 통합을 통해 정교회 신앙을 유지하고 전수해 왔다. 다른 한편으로, 정교회들도 혼합주의의 유혹에 저항하려고 고군분투해 왔다. 그러나 서방에서는 기독교가 강력한 제국의 종교가 되었고, 때로는 박해하는 다수가 되었다. 또한 많은 긍정적인 방식으로 유럽 문명을 형성하는 "주인" 문화가 되었다. 동시에 유대교, 이슬람교, 토착 종교들과의 관계에서 어려움을 겪었다.

14. 종교개혁은 신앙고백과 교파의 확산으로 서구 기독교의 모습을 변화시켰고, 계몽주의는 근대화, 세속화, 개인주의, 교회와 국가의 분리와 함께 문화적 대혁명을 일으켰다. 아시아, 아프리카, 라틴 아메리카 및 세계의 다른 지역으로의 선교 확장은 복음의 토착화와 토착화에 대한 질문을 제기했다. 아시아 종교의 풍부한 영적 유산과 아프리카 전통 종교의 만남은 이들 지역의 문화적, 종교적 유산을 기반으로 한 신학적 전통의 출현으로 이어졌다. 세계 각지에서 은사주의와 오순절교회의 부상은 기독교에 새로운 차원을 추가했다.

15. 간단히 말하자면, 기독교의 "영적 여행"은 매우 복잡한 세계 종교 전통을 만들었다. 기독교는 여러 문화, 종교, 철학적 전통 사이에서 살아가고 현재와 미래의 도전에 대응하려고 노력함에 따라 계속되어 왔고, 변화할 것이다. 이러한 맥락에서 우리는 종교 다원성에 대한 신학적 대응이 필요하다.

종교, 정체성, 문화

16. 타 종교들의 발전 과정도 이와 비슷한 어려움을 겪었다. 유대교, 이슬람교, 힌두교, 불교는 단일 집단의 표현이 아니다. 이 종교들도 원래의 땅을 떠나 여행하면서 이동한 지역의 문화와의 만남에 의해 구체화되고 변형되었다. 오늘날 대부분의 주요 종교들은 다른 종교들에 대한 문화적 "호스트"(hosts, 주류)가 되고 자신의 종교가 아닌 타 종교에 의해 형성된 문화의 "호스트"를 받는 경험을 했다. 이것은 종교 공동체와 그 안에 있는 개인의 정체성이 결코 고정적이지 않으며, 유동적이고 역동적임을 의미한다. 어느 종교도 다른 종교 전통과의 상호 작용에 완전히 영향을 받는 경우는 없다. "종교" 그 자체로 "유대교", "기독교", "이슬람교", "힌두교", "불교" 등을 마치 고정되어 있거나 분화되지 않은 전체(wholes)인 것처럼 말함에는 오히려 오해의 소지가 있다.

17. 이러한 현실은 몇 가지 영적, 신학적 문제를 야기한다. "종교"와 "문화"의 관계는 무엇인가? 그들이 서로에게 미치는 영향의 본질적인 특성은 무엇인가? 우리는 종교적 다원성에 대해 어떤 신학적 의미를 가질 수 있는가? 우리 전통 안의 어떤 자원이 이러한 질문을 처리하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있는가? 우리는 현대 에큐메니칼 운동의 풍부한 유산을 가지고 있다. 이러한 질문은 우리의 탐구에도 도움이 된다.

III. 지속되는 탐구의 진행

에큐메니칼 여정

18. 기독교인들은 초대교회 때부터 그리스도 안에서 증거된 하나님의 사랑의 메시지가 다른 사람들과 공유되어야 한다고 믿었다. 현대 에큐메니칼 운동이 타 종교인들에게도 하나님이 임재한다는 문제에 직면해야 했던 것은 특히 아시아와 아프리카에서 이 메시지를 나누는 과정에서 이루어졌다. 하나님의 계시가 다른 종교와 문화에 있는가? 기독교 계시는 다른 사람들의 종교 생활과 "연속"되어 있는가 아니면 "불연속적"으로 하나님에 대한 지식의 완전히 새로운 차원에서 생겨나는가? 이것은 어려운 질문이고, 기독교인들은 이 문제에 대해 여전히 의견이 불일치하고 있다.

19. WCC의 종교 간의 대화 프로그램은 타 종교의 현실을 존중하고 그 고유성과 정체성을 확인하는 일의 중요성을 강조해 왔다. 또한 정의롭고 평화로운 세상을 모색함에 다른 사람들과 협력해야 할 필요성을 강조했다. 또한 우리와 다른 타 종교에 대해 말하는 방식이 어떻게 대립과 갈등으로 이어질 수 있는가를 깨달았다. 종교는 한편으로 보편적인 진리를 주장한다. 다른 한 편으로는 자기의 주장이 다른 사람들의 진리 주장과 상충될 수 있음을 알고 있다. 이러한 깨달음과 지역 상황에서 서로 다른 종교를 가진 사람들의 만남의 실제 경험은 기독교인들이 "대화"의 관점에서 다른 사람들과의 관계에 대해 말할 수 있는 길을 열어주었다. 그러나 더 많은 탐구를 기다리는 많은 질문이 있다. 관련 커뮤니티가 갈등을 겪고 있을 때 대화를 한다는 것은 무엇을 의미하는가? 개종과 종교의 자유 사이에 인지된 갈등을 어떻게 처리할 것인가? 종교와 인종, 문화적 관습, 국가와의 관계에 대한 여러 신앙 공동체 간의 깊은 차이를 어떻게 다룰 것인가?

20. WCC의 세계선교전도위원회(CWME)의 토론에서 선교사명의 본질과 다양한 종교, 문화 및 이념이 있는 세상에서 그 선교적 위임의 의미에 대한 탐구는 '하나님의 선교'(missio dei)의 개념을 이끌어 냈다. 이것은 우리가 그리스도 안에 참여하도록 부름을 받은 일에 앞서, 세상에 행하는 하나님 자신의 구원사역 곧 일(mission)이 우선이란 것을 알게 했다. 세계선교전도위원회 의제의 몇 가지 문제는 종교다원주의에 대한 현재의 연구와 상호 작용한다. 정의와 평화를 위한 타종교인들과의 협력, 종교 간 대화 참여, 교회의 복음전도 임무 사이의 관계는 무엇인가? 선교에서 토착화 접근을 위한 문화와 종교 사이의 본질적인 관계는 무엇인가? 만약 선교가 2005년 세계선교전도에 관한 컨퍼런스가 시사했듯이 치유와 화해의 공동체 건설에 초점을 맞춘다면 종교간 관계에 대한 의미는 무엇인가?

21.무슬림이 다수인 국가에서 처음으로 모인 WCC의 신앙과직제위원회(2004년 말레이시아 쿠알라룸푸르)는 “신앙의 여정”을 "서로를 받아들이는 비전에서 영감을 받아 고무된 여행이라고 말했다. 그 위원회는 다음과 같이 질문했다. 오늘날의 다종교적 상황에서 교회는 가시적 기독교 일치라는 목표를 어떻게 추구하는가? 교회들 사이에 가시적인 일치를 추구하는 것이 어떻게 사회 전체의 화해를 위한 효과적인 표징이 될 수 있는가? 민족적, 국가적 정체성 문제가 종교적 정체성에 의해 어느 정도 영향을 받는가? 그 반대의 경우도 마찬가지인가? 위원회는 다종교적 맥락에서 발생하는 보다 광범위한 질문을 탐구했다. 기독교인이 다른 사람들에게 "환대하는" 진정한 기독교 신학을 추구하는 데 직면하는 도전은 무엇인가? 다양성의 한계는 무엇인가? 교회 너머에 유효한 구원의 징표가 있는가? 타 종교에서 얻은 통찰이 인간의 의미를 이해하려는 우리에게 어떻게 기여하는가?

22. WCC의 세 가지 실용적인 흐름들은 모두가 종교 신학과 관련된 질문을 다루는 것으로 수렴된다. 이 사실은 의미심장하다. 사실, 최근 컨퍼런스에서 이 논의를 진전시키는 여러 입장을 다루고 공식화하려는 시도가 있었다.

최근의 발전들

23. 우리의 이웃의 종교(타종교) 생활에도 하나님의 구원의 존재하다는 사실에 대한 기독인들 간의 합의를 도출하려고 샌안토니오에서 열린 세계선교대회(1989)에서 WCC는 다음과 같이 확언하도록 입장을 정리했다. “예수 그리스도 외에 다른 구원의 길을 우리가 지정할 수 없음과 동시에 우리는 하나님의 구원하시는 능력을 제한할 수 없다”(We can not point to any other way of salvation than Jesus Christi, at the same time we cannot set limits to the saving power of God). 샌안토니오 보보고서(1989)는 이 진술과 타 종교인들의 삶에 임재하는 하나님과 그 하나님의 일(work)에 대한 확언 사이의 긴장을 인식하고서 "우리는 이 긴장을 높이 평가하고 그것을 해결하려고 시도하지 않는다"고 했다. 이 대회 이후에 등장한 문제는 에큐메니칼 운동이 신학적 겸손의 표현인 이러한 겸손한 말을 하면서 잠자코 있어야 하는가, 아니면 종교 신학을 통해 새롭고 창의적인 공식을 찾아 등장하는 긴장을 해결해야 하는가 하는 것이었다.

24. 샌안토니오 보고서(1989) 내용을 넘어서려고, 스위스 바아르(Baar, 1990)에서 모인 종교 신학에 관한 중요한 성명이 발표되었다. 하나님이 모든 종교들의 창조자이며 유지자로 활동한다는 기독교 신앙의 함의를 이끌어냈다. 모든 민족의 삶, "만물의 창조주인 하나님이 다양한 종교에 현존하고 그 안에서 활동한다는 확신은 하나님의 구원 활동이 어느 한 대륙, 문화 유형 또는 사람들의 그룹에만 국한될 수 있다는 것을 우리에게 상상할 수 없게 한다. 전 세계의 나라들과 민족들 사이에서 발견되는 다양한 여러 종교들의 증언을 진지하게 받아들이려 하지 않는 시도는 만물의 창조주이며 인류의 아버지인 하나님에 대한 성서적 증거를 부인하는 것과 같다“고 했다.

25. 그러므로 WCC의 선교전도위원회, 신앙직제위원회, 종교간의 대화위원회의 흐름의 발전은 오늘날 우리가 종교 신학에 대한 질문을 다시 개최하도록 고무한다. 그러한 탐구는 시급한 신학적 목회적 필요성으로 부상했다. 제9차 WCC 총회의 주제인 "하나님, 당신의 은총에서 세상을 변화시키소서" 역시 그러한 탐구를 요구한다.

IV. 다종교신학을 지향하여

26. 오늘날의 다종교 신학은 어떤 모습일까? 여러 종교 신학들이 제시되었다. 성서 안에 있는 여러 사상의 줄기들은 우리의 과제를 힘들게 만든다(The many streams of thinking within the scriptures make our task challenging). 성서 증거의 다양성을 인정하면서 우리는 "환대"(hospitality)라는 주제를 해석학적 열쇠, 토론의 시작점으로 선택한다.

은총의 하나님의 환대를 칭송하며

27. 종교다원주의에 대한 우리의 신학적 이해는 만물을 창조하신 한 분 하나님 곧 태초부터 모든 피조물에 현존하시고 활동하시는 살아 계신 하나님에 대한 믿음에서 시작된다. 성서는 하나님이 모든 민족과 민족의 하나님이며 모든 인류를 사랑하고 긍휼히 여기는 하나님이심을 증언한다. 우리는 노아와의 언약에서 결코 깨지지 않은 모든 피조물과의 언약을 본다. 우리는 하나님께서 지혜와 총명의 전통(타 종교들, 역자 주)을 통해 열방을 인도할 때 하나님의 지혜와 정의가 땅 끝까지 확장되는 것을 본다. 하나님의 영광은 모든 피조물을 관통한다. 히브리어 성서는 말씀 혹은 지혜와 성령을 통해 인류 역사 전체에 걸쳐 임하는 하나님의 보편적인 구원을 증언한다.(따라서 모든 종교들은 하나님의 활동의 결과물이며, 구원의 길이라는 뜻. 역자 주).

28. 신약성서에서 사도 바울은 하나님 말씀의 성육신을 환대(hospitality)와 타자에 대한 삶의 방향전환의 용어로 말씀했다. 바울은 다음과 같이 송영의 언어로 말했다. “그(그리스도)는 근본 하나님의 본체시나 하나님과 동등됨을 취할 것으로 여기지 아니하시고 오히려 자기를 비어 종의 형체를 가져 사람과 같이 되셨느니라. 사람의 모양으로 나타나사 자기를 낮추시고 죽기까지 복종하셨으니 곧 십자가에 죽으심이라"(빌 2:6-8). 그리스도의 자기 비움과 기꺼이 우리의 인성을 취한 것은 우리 신앙 고백의 핵심이다. 성육신의 신비는 하나님과 우리 인간의 조건을 가장 깊숙이 동일시하는 것이며, 타자이고 소외되어 있는 인간을 받아들인 하나님의 무조건적인 은총을 보여준다. 바울은 계속해서 부활하신 그리스도를 칭송한다. "그러므로 하나님이 그를 지극히 높여 모든 이름 위에 뛰어난 이름을 주셨느니라"(빌 2:9). 이것은 기독교인들을 예수 그리스도께서 전 인류, 전 인간 가족(타종교 포함, 역자 주)을 끊을 수 없는 끈과 약 언약으로 하나님께 결합시켜 주었다는 고백으로 이끈다.

29. 예수 그리스도 안에 나타난 이 하나님의 은총은 우리가 다른 사람들과의 관계에서 환대하는 태도를 갖도록 요구한다. 바울은 "그리스도 예수의 마음을 너희도 품으라"(빌 2:5)라고 말하면서 찬송을 시작한다. 우리의 환대는 자기 비움을 포함하며, 무조건적인 사랑으로 다른 사람들을 받아들임으로써 우리는 하나님의 구속하는 사랑의 본에 참여한다. 실제로 우리의 환대는 우리 공동체(기독교) 구성원에만 국한되는 것이 아니다. 복음은 원수까지도 사랑하고 그들에게 축복을 구하라고 명령한다(마 5:43-48, 롬 12:14). 그러므로 그리스도인인 우리는 그리스도 안에 있는 우리의 정체성과 바로 그 정체성에서 나오는 케노틱(자기비움) 사랑을 본받아 타자에게 마음의 문을 여는 일 사이에서 올바른 균형을 찾아낼 필요가 있다.

30. 예수는 공생애를 통해 자신의 전통에 속한 사람들을 치유했을 뿐만 아니라 가나안 여인과 로마 백부장의 큰 믿음에 응답했다(마 15:21-28, 8:5-11). 예수는 긍휼과 환대를 통해 이웃을 사랑하라는 계명의 성취를 보여주려고 "나그네"(낯선 사람, 이방인, stranger)인 사마리아인을 선택했다. 복음서는 예수님과 다른 신앙을 가진 사람들과의 만남을 주요 사역의 일부가 아니라 부수적인 것으로 제시한다. 그렇기 때문에 이러한 이야기는 종교 신학에 대한 명확한 결론을 내리는 데 필요한 정보를 제공하지 않는다. 그러나 그들은 예수를 사랑과 인정이 필요한 모든 사람에게 환대를 베푸신 분으로 제시한다. 마지막 심판에 대한 예수님의 비유에 대한 마태의 이야기는 더 나아가 부활한 그리스도와 교통하는 예기치 못한 방법으로 사회의 희생자들에 대한 열린 마음, 낯선 사람들에 대한 환대, 타자 수용을 확인시켜 준다(마 25:31-46).

31. 예수께서 사회의 주변부 사람들에게 환대를 베푸셨지만 그 분 자신도 거절을 당해야 했고 종종 환대를 필요로 했다는 사실은 의미심장하다. 예수께서 주변 사람들을 받아들인 것과 거절당한 경험은 우리 시대에 가난한 자들, 멸시받는 자들, 버림받은 자들과 연대하는 사람들에게 영감을 주었다. 따라서 환대에 대한 성서적 이해는 타자에게 도움을 베풀고 관대함을 보이는 일반적인 개념을 훨씬 뛰어넘는다. 성서는 환대를 일차적으로 모든 사람의 존엄성에 대한 확언에 기초하여 타자에게 근본적으로 마음 문을 개방하는 것이라고 말한다. 우리는 이웃을 사랑하라는 예수님의 모범과 그분의 명령에서 영감을 얻는다.

32. 성령은 우리가 타자에게 그리스도의 열린 마음을 실천하도록 돕는다. 성령의 인격은 창조, 양육, 유지, 도전하고, 새롭게 하고, 변화시키려고 지상에 운행했고 지금도 운행한다. 우리는 성령의 활동이 "바람이 임의로 불듯이"(요 3:8)의 방식으로 우리의 정의, 설명 및 제한을 초월한다는 것을 고백한다(정의, 설명, 제한은 예수가 유일한 그리스도이며 구원의 길이며 중보자이라라고 정의하거나 설명하거나 예수를 믿어야 구원을 받는다라는 등의 제한을 의미한다, 역자 주). 우리의 희망과 기대는 성령의 "경륜"이 전체 피조물(종교들 포함, 역자 주)과 관련되어 있다는 우리의 믿음에 뿌리를 두고 있다. 우리는 하나님의 영이 우리가 예측할 수 없는 방식으로 움직인다고 이해한다. 우리는 성령의 양육하는 능력이 인간 내부에서 역사하고 진리와 평화와 정의를 갈망하고 추구하는 보편적인 모든 인간에게 영감을 주고 있음을 본다(롬 8:18-27). "사랑과 희락과 화평과 오래 참음과 자비와 관대함과 충성과 온유와 절제"는 어디에서나(타종교 포함, 역자 주) 성령의 열매이다(갈 5:22-23, 롬 14:17 참조).

33. 우리는 이 포괄적인 성령의 역사가 '살아있는 믿음의 사람들'(타종교인들, 역자 주)의 삶과 전통(종교, 역자 주)에도 존재한다고 믿는다. 모든 사람들은 항상 어디서나 그들 가운데 계신 하나님의 임재와 활동에 반응해 왔으며, 살아 계신 하나님과의 만남을 증언해 왔다. 이 증언으로 그들은 온전함, 깨달음, 신적 인도, 안식, 해방을 추구하고 발견한 것에 대하여 말한다. 이것이 우리 그리스도인들이 그리스도를 통해 경험한 구원에 대해 증언하는 콘텍스트이다. 타 종교인 우리의 이웃들 사이에서 이루어지는 이 증거 사역은 "하나님이 그들(타종교인들) 가운데서 행하시고 행하신 일에 대한 확증"을 전제로 해야 한다(CWME, San Antonio 1989).(하나님이 타종교 가운데 행하는 일 곧 사랑, 은혜, 구원 활동과 성령의 열매 등을 의미한다. 역자 주).

34. 우리는 종교다원주의를 하나님께서 사람들과 나라들과 관계를 맺으신 다양한 방식의 결과로 볼 뿐만 아니라 하나님의 은총의 선물에 대한 인간의 반응의 풍요로움과 다양성의 표현이라고 본다. 항상 이러한 분별력의 은사를 사용하여 종교다원주의의 전 영역을 진지하게 받아들이도록 도전하는 것은 하나님을 믿는 우리의 기독교인의 신앙이다. "하나님이 다른 종교를 가진 남녀 사람들에게 주신 지혜, 사랑, 능력"(New Delhi report, 1961)에 대한 새롭고 더 큰 이해를 발전시키기 위해, 우리는 "예수 그리스도 안에서 하나님이 우리를 만나듯이 타 종교인 이웃들의 삶에서 만날 수 있는 가능성에 대한 개방성"을 확언해야 한다(CWME, San Antonio 1989). (the God we know in Jesus Christ may encounter us also in the lives of our neighbours of other faiths). 우리는 또한 진리의 영인 성령께서 우리에게 이미 주어진 믿음의 유산을 새롭게 이해하고, 타종교 신앙을 가진 이웃들로부터 더 많은 것을 배울 때 신성한 신비(divine mystery)에 대한 신선하고 예상치 못한 통찰력으로 우리를 인도하실 것이라고 믿는다.

35. 따라서 삼위일체 하나님, 단일성의 다양성인 하나님, 모든 생명을 창조하고 온전케 하고 양육하고 기르는 하나님에 대한 우리의 믿음은 모든 사람에게 열린 마음으로 환대할 수 있도록 돕는다. 우리는 하나님의 너그러운 사랑의 환대를 받은 사람들이다. 우리는 달리 행동할 수 없다.

V. 환대에 대한 부름

36. 그리스도인들은 하나님의 관대함과 은총에 어떻게 반응해야 하는가? "나그네 대접하기를 게을리 하지 말라 이로써 부지중에 천사들을 대접한 사람들도 있느니라"(히 13:2). 오늘의 콘텍스트에서 "나그네"(낯선 사람, 이방인) 범주에는 우리에게 알려지지 않은 사람들, 가난한 사람들, 착취당하는 사람들뿐만 아니라 인종적, 문화적, 종교적으로 우리에게 "타인"도 포함된다. 성서에서 "나그네"(이방인)라는 단어는 "타자"를 객관화하려는 것이 아니라 문화, 종교, 인종 및 인간 공동체의 일부인 다른 종류의 다양성에서 우리에게 참으로 "나그네"인 사람들이 있음을 인정하게 한다. 다른 사람들을 우리가 기꺼이 받아들이는 것은 진정한 환대의 전형적인 특징이다. "타자"에 대하여 마음을 엶으로써 우리는 새로운 방식으로 하나님을 만날 수도 있다. 따라서 환대는 "이웃을 내 몸과 같이 사랑하라"는 계명의 실행이며 하나님을 새롭게 발견할 수 있는 기회이다.

37. 환대는 또한 우리가 그리스도인 가족 안에서 서로를 대하는 방법과도 관련이 있다. 때때로 우리는 외부의 사람들만큼이나 서로에게 낯설다. 변화하는 세계 상황, 특히 이동성과 인구 이동의 증가로 인해 때때로 우리는 다른 사람들를 초대하는 "주인"(hosts)이 되기도 하고 다른 사람들의 환대를 받는 "손님"(guests)이 되기도 한다. 우리는 때로 "나그네"(이방인, 낯선 사람)를 받아들이고 다른 사람 사이에서 "나그네"가 될 때도 있다. 실제로 우리는 환대를 "주인"과 "손님"의 구분을 초월하는 "상호 개방성"으로 이해해야 할 필요가 있다.

38. 환대는 다른 사람들과 관계를 맺는 쉽고 간단한 방편이 아니다. 환대는 종종 기회일 뿐만 아니라 위험이기도 한다. 정치적 또는 종교적 긴장이 있는 상황에서 환대 행위는 큰 용기를 필요로 할 수 있다. 특히 우리와 깊이 동의하지 않거나 심지어 우리를 적으로 여기는 사람들을 대할 때 그렇다. 또한, 당사자 간의 불평등, 왜곡된 권력 관계 또는 숨겨진 의제가 있을 때 대화는 매우 어렵다. 또한 때때로 환대를 제공하거나 환대를 받은 바로 그 사람들의 깊은 신념에 의문을 제기하고 그 대가로 자신의 신념에 도전해야 하는 의무감을 느낄 수도 있다.

상호 변환의 힘

39. 그리스도인들은 타종교인들과 공존하는 법을 배웠을 뿐만 아니라 그들의 만남을 통해 변화되기도 했다. 우리는 세상(타종교 포함, 역자 주)에 있는 하나님의 임재에 대한 알려지지 않은 측면을 발견했고, 우리 자신의 기독교 전통에서 무시된 요소를 발견했다(성서가 종교다원주의를 지지한다는 의미, 역자 주). 우리는 또한 타인에게 더 잘 반응하도록 요구하는 성서의 많은 구절을 더 많이 인식하게 되었다.

40. 낯선 사람에 대한 실제적인 환대와 나그네를 환영하는 태도는 상호 변화와 화해의 공간을 만든다. 이러한 상호성은 믿음의 조상 아브라함과 이스라엘 사람이 아닌 살렘 왕 멜기세덱의 만남 이야기(창 14장)에 잘 나타나 있다. 아브라함은 '지극히 높으신 하나님'의 제사장으로 묘사되는 멜기세덱의 축복을 받았다. 이야기는 이 만남을 통해 아브라함과 우르와 하란에서 그와 그의 가족을 인도한 하나님의 본질에 대한 아브라함의 이해가 새로워지고 확장되었음을 시사한다.

41. 사도행전에서 베드로와 고넬료의 만남에 대한 누가의 이야기에도 상호 변화가 담겨 있다. 성령은 베드로가 본 환상과 고넬료와의 상호작용을 통해 자기 이해의 변화시켰다. 이로 말미암아 그는 "하나님은 사람을 외모로 취하지 아니하시고 각 나라 중 하나님을 경외하며 의를 행하는 자는 다 받으신다"(행 10:34-35)고 고백하게 되었다. 이 경우 베드로가 고넬료와 그의 가족을 변화시키는 도구가 된 것처럼 "이방인" 고넬료는 베드로의 변화의 도구가 된었다. 이 이야기가 주로 종교 간 관계에 관한 것은 아니지만, 하나님께서 우리가 타자와 만남에서 자기 이해의 한계를 넘어서도록 하나님이 어떻게 인도할 수 있는지에 대하여 빛을 비춰준다.

42. 따라서 우리는 이러한 예와 일상생활의 풍부한 경험에서 다양한 종교인들 사이의 상호 환대의 비전이라는 결과를 도출할 수 있다. 기독교적 관점에서 이것은 우리의 화해 사역과 많은 관련이 있다. 그것은 그리스도 안에 있는 하나님에 대한 "타자"에 대한 우리의 증거와 하나님께서 "타자"를 통해 우리에게 말씀하실 수 있도록 우리에게 개방성을 가질 것을 전제로 한다. 이런 관점에서 이해된 선교에는 승리주의의의 여지가 없다. 이것은 종교적 적개심과 그에 수반되는 폭력의 원인을 제거하는 데 이바지한다. 환대는 기독교인들이 다른 사람들을 하나님의 형상대로 창조된 존재로 받아들일 것을 요구하며, 하나님께서 다른 사람들을 변화시키려고 우리를 사용하는 것처럼 하나님께서 우리를 가르치고 변화시키려고 다른 사람들을 통해 우리에게 말씀하실 수도 있다는 것을 알도록 요구한다.

43. 성서 이야기와 에큐메니칼 사역의 경험은 이러한 상호 변화가 진정한 기독교 증거의 핵심임을 보여준다. "타자"에 대한 개방성은 그것이 우리를 변화시킬 수 있는 것처럼 "타자"를 변화시킬 수 있다. 그것은 다른 사람들에게 기독교와 복음에 대한 새로운 관점을 줄 수 있다. 또한 새로운 관점에서 자신의 신앙을 이해할 수 있게 한다. 열린 마음 곧 개방성과 그로부터 오는 변화는 차례로 놀라운 방식으로 우리의 삶을 풍요롭게 할 수 있다.

VI. 구원은 하나님께 있다

44. 인류 종교들의 거대 다양성은 진리를 찾으려고 떠나는 인간의 성취를 향한 "여행" 또는 "순례"이다. 우리가 서로에게 “나그네"(낯선 사람)일지라도 "종교적 환대"가 필요한 우리의 길이 교차하는 순간이 있다. 오늘날 우리의 개인적인 경험과 과거의 역사적 순간 모두 그러한 환대가 가능하고 작은 방식으로 이루어졌다는 사실을 증거한다.

45. 그러한 환대를 확대하는 것은 "타자"를 환대하는 신학에 달려 있다. 하나님에 대한 성서의 증언의 특징과 우리가 믿는 하나님이 그리스도 안에서 행하신 일 그리고 성령의 역사에 대한 우리의 성찰은 “타자”를 포용하는 환대의 자세가 기독교 신앙의 핵심이라는 사실을 보여준다. 치유와 화해가 필요한 세상에서 종교 신학에 영감을 주는 것은 바로 이러한 정신(환대, 종교다원주의 신념, 역자 주)이다. 이 정신이야말로 자기의 종교적 신념과 상관없이 사회의 주변부로 밀려난 모든 사람들과 우리의 연대를 가져다 준다.

46. 우리는 인간의 한계와 언어의 한계로 말미암아, 어느 공동체도 하나님께서 인류에게 베푸는 구원의 신비를 샅샅이 헤아릴 수 없음을 인정해야 한다. (기독교만이 진리를 독점한다는 발상은 틀렸다는 뜻, 역자 주). 과거의 분석에서 우리의 모든 신학적 심사숙고기 우리 자신의 경험에 의해 제한되어 있었다. 그것이 세상을 고치시는 하나님의 사역의 범위를 온전히 설정할 것이라고 희망할 수 없다.(예수를 믿어야 구원을 얻는다고 말할 수 없다는 뜻, 역자 주).

47. 우리가 구원은 하나님께, 오직 하나님께 속한다고 말할 수 있는 것은 바로 이러한 겸손이다. 우리는 구원을 소유하고 있지 않으며, 그것에 참여할 뿐이다. 구원을 베푸는 주체는 우리가 아니다. 우리는 그것을 증거할 뿐이다. 우리는 누가 구원을 받을지 결정하지 않고, 그것을 하나님의 섭리에 맡길 뿐이다(타종교에 구원이 없다고 말할 수 없다는 뜻이다, 역자 주). 구원의 “주인”(host)는 바로 하나님이다. 그러나 새 하늘과 새 땅에 대한 종말론적 환상 속에, 우리는 우리에게 “주인”도 되고 “손님”도 되는 하나님의 강력한 상징을 가지고 있기도 하다. "하나님이 그들과 함께 계시리니 그들은 하나님의 백성이 되리라. 하나님은 친히 그들과 함께 계시리라"(계 21:3).

한글번역 최덕성

http://www.oikoumene.org/en/resources/documents/assembly/porto-alegre-2006/3-preparatory-and-background-documents/religious-plurality-and-christian-self-understanding.html? Document date: 14.02.2006

Religious Plurality and Christian Self-Understanding

World Council of Churches

The present document is the result of a study process in response to suggestions made in 2002 at the WCC central committee to the three staff teams on Faith and Order, Inter-religious Relations, and Mission and Evangelism, and their respective commissions or advisory bodies. The question of the theological approach to religious plurality had been on the agenda of the WCC many times, reaching a certain consensus in 1989 and 1990.1 In recent years, it was felt that this difficult and controversial issue needed to be revisited.

Some twenty scholars from different contexts and denominations, specialized in religious studies, missiology or systematic theology and part of the networks of the three teams, worked for two years in a significant effort of cooperation between different constituencies in the recent history of the WCC.

It must be emphasized that the paper does not represent the view of the WCC. Discussions in commissions showed how important but also how controversial the matter is. Much careful theological work is needed. This document is shared as a background document for discussion and debate. Further comments, critiques and suggestions from assembly participants or churches and other partners are welcome and will be fed into the continuing reflection on the key issue of Christian self-understanding and witness in a religiously plural world.2

Preamble

The earth is the Lord's and all that is in it, the world, and those who live in it (Ps. 24:1).

For from the rising of the sun to its setting my name is great among the nations, and in every place incense is offered to my name, and a pure offering; for my name is great among the nations, says the Lord of hosts (Mal. 1:11).

Then Peter began to speak to them: "I truly understand that God shows no partiality, but in every nation anyone who fears him and does what is right is acceptable to him" (Acts 10:34-35).

1. What do the experiences of the psalmist, the prophet and Peter mean for us today? What does it mean to affirm our faith in Jesus Christ joyfully, and yet seek to discern God's presence and activity in the world? How do we understand such affirmations in a religiously plural world?

I. The challenge of plurality

2. Today Christians in almost all parts of the world live in religiously plural societies. Persistent plurality and its impact on their daily lives are forcing them to seek new and adequate ways of understanding and relating to peoples of other religious traditions. The rise of religious extremism and militancy in many situations has accentuated the importance of inter-religious relations. Religious identities, loyalties, and sentiments have become important components in so many international and inter-ethnic conflicts that some say that the "politics of ideology", which played a crucial role in the 20th century, has been replaced in our day by the "politics of identity".

3. All religious communities are being reshaped by new encounters and relationships. Globalization of political, economic, and even religious life brings new pressures on communities that have been in geographical or social isolation. There is greater awareness of the interdependence of human life, and of the need to collaborate across religious barriers in dealing with the pressing problems of the world. All religious traditions, therefore, are challenged to contribute to the emergence of a global community that would live in mutual respect and peace. At stake is the credibility of religious traditions as forces that can bring justice, peace and healing to a broken world.

4. Most religious traditions, however, have their own history of compromise with political power and privilege and of complicity in violence that has marred human history. Christianity, for instance, has been, on the one hand, a force that brought the message of God's unconditional love for and acceptance of all people. On the other hand, its history, sadly, is also marked by persecutions, crusades, insensitivity to Indigenous cultures, and complicity with imperial and colonial designs. In fact, such ambiguity and compromise with power and privilege is part of the history of all religious traditions, cautioning us against a romantic attitude towards them. Further, most religious traditions exhibit enormous internal diversity attended by painful divisions and disputes.

5. Today these internal disputes have to be seen in the light of the need to promote mutual understanding and peace among the religions. Given the context of increased polarization of communities, the prevalent climate of fear, and the culture of violence that has gripped our world, the mission of bringing healing and wholeness to the fractured human community is the greatest challenge that faces the religious traditions in our day.

The changing context of the Christian faith.

6. The global religious situation is also in flux. In some parts of the Western world, the institutional expressions of Christianity are in decline. New forms of religious commitment emerge as people increasingly separate personal faith from institutional belonging. The search for authentic spirituality in the context of a secular way of life presents new challenges to the churches. Further, peoples of other traditions, like Hindus, Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs, etc., who have increasingly moved into these areas, as minorities, often experience the need to be in dialogue with the majority community. This challenges Christians to be able to articulate their faith in ways that are meaningful both to them and their neighbours; dialogue presupposes both faith commitment and the capacity to articulate it in word and deed.

7. At the same time, Christianity, especially in its evangelical and Pentecostal manifestations, is growing rapidly in some regions of the world. In some of the other regions, Christianity is undergoing radical changes as Christians embrace new and vibrant forms of church life and enter into new relationships with indigenous cultures. While Christianity appears to be on the decline in some parts of the world, it has become a dynamic force in others.

8. These changes require us to be more attentive than before to our relationship with other religious communities. They challenge us to acknowledge "others" in their differences, to welcome strangers even if their "strangeness" sometimes threatens us, and to seek reconciliation even with those who have declared themselves our enemies. In other words, we are being challenged to develop a spiritual climate and a theological approach that contributes to creative and positive relationships among the religious traditions of the world.

9. The cultural and doctrinal differences among religious traditions, however, have always made inter-religious dialogue difficult. This is now aggravated by the tensions and animosities generated by global conflicts and mutual suspicions and fears. Further, the impression that Christians have turned to dialogue as a new tool for their mission, and the controversies over "conversion" and "religious freedom", have not abated. Therefore dialogue, reconciliation and peace-building across the religious divides have become urgent, and yet they are never achieved through isolated events or programs. They involve a long and difficult process sustained by faith, courage and hope.

The pastoral and faith dimensions of the question.

10. There is a pastoral need to equip Christians to live in a religiously plural world. Many Christians seek ways to be committed to their own faith and yet to be open to the others. Some use spiritual disciplines from other religious traditions to deepen their Christian faith and prayer life. Still others find in other religious traditions an additional spiritual home and speak of the possibility of "double belonging". Many Christians ask for guidance to deal with interfaith marriages, the call to pray with others, and the need to deal with militancy and extremism. Others seek for guidance as they work together with neighbours of other religious traditions on issues of justice and peace. Religious plurality and its implications now affect our day-to-day lives.

11. As Christians we seek to build a new relationship with other religious traditions because we believe it to be intrinsic to the gospel message and inherent to our mission as co-workers with God in healing the world. Therefore the mystery of God's relationship to all God's people, and the many ways in which peoples have responded to this mystery, invite us to explore more fully the reality of other religious traditions and our own identity as Christians in a religiously plural world.

II. Religious traditions as spiritual journeys

The Christian journey

12. It is common to speak of religious traditions being "spiritual journeys". Christianity's spiritual journey has enriched and shaped its development into a religious tradition. It emerged initially in a predominantly Jewish-Hellenistic culture. Christians have had the experience of being "strangers", and of being persecuted minorities struggling to define themselves in the midst of dominant religious and cultural forces. And as Christianity grew into a world religion, it has become internally diversified, transformed by the many cultures with which it came into contact.

13. In the East, the Orthodox churches have throughout their history been involved in a complex process of cultural engagement and discernment, maintaining and transmitting the Orthodox faith through integration of select cultural aspects over the centuries. On the other hand, the Orthodox churches have also struggled to resist the temptation towards syncretism. In the West, having become the religious tradition of a powerful empire, Christianity has at times been a persecuting majority. It also became the "host" culture, shaping European civilization in many positive ways. At the same time, it has had a troubled history in its relationship with Judaism, Islam, and Indigenous traditions.

14. The Reformation transformed the face of Western Christianity, introducing Protestantism with its proliferation of confessions and denominations, while the Enlightenment brought about a cultural revolution with the emergence of modernity, secularization, individualism, and the separation of church and state. Missionary expansions into Asia, Africa, Latin America and other parts of the world raised questions about the indigenization and inculturation of the gospel. The encounter between the rich spiritual heritage of the Asian religions and the African Traditional Religions resulted in the emergence of theological traditions based on the cultural and religious heritages of these regions. The rise of charismatic and Pentecostal churches in all parts of the world has added yet a new dimension to Christianity.

15. In short, the "spiritual journey" of Christianity has made it a very complex worldwide religious tradition. As Christianity seeks to live among cultures, religions and philosophic traditions and attempts to respond to the present and future challenges, it will continue to be transformed. It is in this context, of a Christianity that has been and is changing, that we need a theological response to plurality.

Religions, identities and cultures.

16. Other religious traditions have also lived through similar challenges in their development. There is no one expression of Judaism, Islam, Hinduism or Buddhism, etc. As these religions journeyed out of their lands of origin they too have been shaped by the encounters with the cultures they moved into, transforming and being transformed by them. Most of the major religious traditions today have had the experience of being cultural "hosts" to other religious traditions, and of being "hosted" by cultures shaped by religious traditions other than their own. This means that the identities of religious communities and of individuals within them are never static, but fluid and dynamic. No religion is totally unaffected by its interaction with other religious traditions. Increasingly it has become rather misleading even to talk of "religions" as such, and of "Judaism", "Christianity", "Islam", "Hinduism", "Buddhism", etc., as if they were static, undifferentiated wholes.

17. These realities raise several spiritual and theological issues. What is the relationship between "religion" and "culture"? What is the nature of the influence they have on one another? What theological sense can we make of religious plurality? What resources within our own tradition can help us deal with these questions? We have the rich heritage of the modern ecumenical movement's struggle with these questions to help us in our exploration.

III. Continuing an ongoing exploration

The ecumenical journey

18. From the very beginnings of the church, Christians have believed that the message of God's love witnessed to in Christ needs to be shared with others. It is in the course of sharing this message, especially in Asia and Africa, that the modern ecumenical movement had to face the question of God's presence among people of other traditions. Is God's revelation present in other religions and cultures? Is the Christian revelation in "continuity" with the religious life of others, or is it "discontinuous", bringing in a whole new dimension of knowledge of God? These were difficult questions and Christians remain divided over the issue.

19. The dialogue programme of the World Council of Churches (WCC) has emphasized the importance of respecting the reality of other religious traditions and affirming their distinctiveness and identity. It has also brought into focus the need to collaborate with others in the search for a just and peaceful world. There is also greater awareness of how our ways of speaking about our and other religious traditions can lead to confrontations and conflicts. On the one hand, religious traditions make universal truth claims. On the other hand, these claims by implication may be in conflict with the truth claims of others. These realizations, and actual experiences of relationships between peoples of different traditions in local situations, opened the way for Christians to speak of our relationship with others in terms of "dialogue". Yet, there are many questions awaiting further exploration. What does it mean to be in dialogue when the communities concerned are in conflict? How does one deal with the perceived conflict between conversion and religious freedom? How do we deal with the deep differences among faith communities over the relationship of religious traditions to ethnicity, cultural practices and the state?

20. Within the discussions in the commission on World Mission and Evangelism (CWME) of the WCC the exploration of the nature of the missionary mandate and its implications in a world of diverse religions, cultures and ideologies have drawn on the concept of missio Dei, God's own salvific mission in the world, even preceding human witness, in which we are in Christ called to participate. Several issues of CWME's agenda interact with the present study on religious plurality: What is the relation between cooperation with people of other religious traditions (for justice and peace), involvement in inter-religious dialogue, and the evangelistic mandate of the church? What are the consequences of the intrinsic relation between cultures and religions for the inculturation approach in mission? What are the implications for interfaith relations if mission focuses, as the 2005 conference on world mission and evangelism suggests, on building healing and reconciling communities?

21. The WCC's plenary commission on Faith and Order, meeting for the first time in a Muslim-majority country (in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2004) spoke of the "journey of faith" as one inspired by the vision of "receiving one another". The commission asked: How do the churches pursue the goal of visible Christian unity within today's increasingly multi-religious context? How can the search for visible unity among the churches be an effective sign for reconciliation in society as a whole? To what extent are questions of ethnic and national identity affected by religious identities and vice versa? The commission also explored broader questions arising in multi-religious contexts: What are the challenges which Christians face in seeking an authentic Christian theology that is "hospitable" to others? What are the limits to diversity? Are there valid signs of salvation beyond the church? How do insights from other traditions contribute to our understanding of what it means to be human?

22. It is significant that all three programmatic streams of the WCC converge in dealing with questions that are relevant for a theology of religions. In fact, attempts have been made in recent conferences to deal with, and formulate, positions that take the discussions forward.

Recent developments.

23. In its search for consensus among Christians about God's saving presence in the religious life of our neighbours, the world mission conference in San Antonio (1989) summed up the position that the WCC has been able to affirm: "We cannot point to any other way of salvation than Jesus Christ; at the same time we cannot set limits to the saving power of God." Recognizing the tension between such a statement and the affirmation of God's presence and work in the life of peoples of other faith traditions, the San Antonio report said that "we appreciate this tension, and do not attempt to resolve it". The question following the conference was whether the ecumenical movement should remain with these modest words as an expression of theological humility, or whether it should deal with that tension in finding new and creative formulations in a theology of religions.

24. In an attempt to go beyond San Antonio, a WCC consultation on theology of religions in Baar, Switzerland (1990), produced an important statement, drawing out the implications of the Christian belief that God is active as Creator and Sustainer in the religious life of all peoples: "This conviction that God as Creator of all is present and active in the plurality of religions makes it inconceivable to us that God's saving activity could be confined to any one continent, cultural type, or group of people. A refusal to take seriously the many and diverse religious testimonies to be found among the nations and peoples of the whole world amounts to disowning the biblical testimony to God as Creator of all things and Father of humankind."

25. Hence, developments in the Mission and Evangelism, Faith and Order, and Dialogue streams of the WCC encourage us to reopen the question of the theology of religions today. Such an inquiry has become an urgent theological and pastoral necessity. The theme of the ninth WCC assembly, "God, in Your Grace, Transform the World", also calls for such an exploration.

IV. Towards a theology of religions

26. What would a theology of religions look like today? Many theologies of religions have been proposed. The many streams of thinking within the scriptures make our task challenging. While recognizing the diversity of the scriptural witness, we choose the theme of "hospitality" as a hermeneutical key and an entry point for our discussion.

Celebrating the hospitality of a gracious God.

27. Our theological understanding of religious plurality begins with our faith in the one God who created all things, the living God present and active in all creation from the beginning. The Bible testifies to God as God of all nations and peoples, whose love and compassion includes all humankind. We see in the covenant with Noah a covenant with all creation that has never been broken. We see God's wisdom and justice extending to the ends of the earth, as God guides the nations through their traditions of wisdom and understanding. God's glory penetrates the whole of creation. The Hebrew Bible witnesses to the universal saving presence of God throughout human history through the Word or Wisdom and the Spirit.

28. In the New Testament, the incarnation of the Word of God is spoken of by St. Paul in terms of hospitality and of a life turned towards the "other". Paul proclaims, in doxological language, that "though he (Christ) was in the form of God he did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death - even death on a cross" (Phil. 2:6-8). The self-emptying of Christ, and his readiness to assume our humanity, is at the heart of the confession of our faith. The mystery of the incarnation is God's deepest identification with our human condition, showing the unconditional grace of God that accepted humankind in its otherness and estrangement. Paul's hymn moves on to celebrate the risen Christ: "Therefore God has highly exalted him, and given him the name that is above every name" (Phil. 2:9). This has led Christians to confess Jesus Christ as the one in whom the entire human family has been united to God in an irrevocable bond and covenant.

29. This grace of God shown in Jesus Christ calls us to an attitude of hospitality in our relationship to others. Paul prefaces the hymn by saying, "Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus" (Phil. 2:5). Our hospitality involves self-emptying, and in receiving others in unconditional love we participate in the pattern of God's redeeming love. Indeed our hospitality is not limited to those in our own community; the gospel commands us to love even our enemies and to call for blessings upon them (Matt.5:43-48; Rom.12:14). As Christians, therefore, we need to search for the right balance between our identity in Christ and our openness to others in kenotic love that comes out of that very identity.

30. In his public ministry, Jesus not only healed people who were part of his own tradition but also responded to the great faith of the Canaanite woman and the Roman centurion (Matt. 15:21-28, 8:5-11). Jesus chose a "stranger", the Samaritan, to demonstrate the fulfilling of the commandment to love one's neighbour through compassion and hospitality. Since the gospels present Jesus' encounter with those of other faiths as incidental, and not as part of his main ministry, these stories do not provide us with the necessary information to draw clear conclusions regarding any theology of religions. But they do present Jesus as one whose hospitality extended to all who were in need of love and acceptance. Matthew's narrative of Jesus' parable of the last judgment goes further to identify openness to the victims of society, hospitality to strangers and acceptance of the other as unexpected ways of being in communion with the risen Christ (25:31-46).

31. It is significant that while Jesus extended hospitality to those at the margins of society he himself had to face rejection and was often in need of hospitality. Jesus' acceptance of the peoples at the margins, as well as his own experience of rejection has provided the inspiration for those who show solidarity in our day with the poor, the despised and the rejected. Thus the biblical understanding of hospitality goes well beyond the popular notion of extending help and showing generosity towards others. The Bible speaks of hospitality primarily as a radical openness to others based on the affirmation of the dignity of all. We draw our inspiration both from Jesus' example and his command that we love our neighbours.

32. The Holy Spirit helps us to live out Christ's openness to others. The person of the Holy Spirit moved and still moves over the face of the earth to create, nurture and sustain, to challenge, renew and transform. We confess that the activity of the Spirit passes beyond our definitions, descriptions, and limitations in the manner of the wind that "blows where it wills" (John 3:8). Our hope and expectancy are rooted in our belief that the "economy" of the Spirit relates to the whole creation. We discern the Spirit of God moving in ways that we cannot predict. We see the nurturing power of the Holy Spirit working within, inspiring human beings in their universal longing for, and seeking after, truth, peace and justice (Rom. 8:18-27). "Love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control", wherever they are found, are the fruit of the Spirit (Gal. 5:22-23, cf. Rom. 14:17).

33. We believe that this encompassing work of the Holy Spirit is also present in the life and traditions of peoples of living faith. People have at all times and in all places responded to the presence and activity of God among them, and have given their witness to their encounters with the living God. In this testimony they speak both of seeking and of having found wholeness, or enlightenment, or divine guidance, or rest, or liberation. This is the context in which we as Christians testify to the salvation we have experienced through Christ. This ministry of witness among our neighbours of other faiths must presuppose an "affirmation of what God has done and is doing among them" (CWME, San Antonio 1989).

34. We see the plurality of religious traditions as both the result of the manifold ways in which God has related to peoples and nations as well as a manifestation of the richness and diversity of human response to God's gracious gifts. It is our Christian faith in God which challenges us to take seriously the whole realm of religious plurality, always using the gift of discernment. Seeking to develop new and greater understandings of "the wisdom, love and power which God has given to men (and women) of other faiths" (New Delhi report, 1961), we must affirm our "openness to the possibility that the God we know in Jesus Christ may encounter us also in the lives of our neighbours of other faiths" (CWME, San Antonio 1989). We also believe that the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of Truth, will lead us to understand anew the deposit of the faith already given to us, and into fresh and unforeseen insight into the divine mystery, as we learn more from our neighbours of other faiths.

35. Thus, it is our faith in the trinitarian God, God who is diversity in unity, God who creates, brings wholeness, and nurtures and nourishes all life, which helps us in our hospitality of openness to all. We have been the recipients of God's generous hospitality of love. We cannot do otherwise.

V. The call to hospitality

36. How should Christians respond in light of the generosity and graciousness of God? "Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for by doing that some have entertained angels without knowing it" (Heb. 13:2). In today's context the "stranger" includes not only the people unknown to us, the poor and the exploited, but also those who are ethnically, culturally and religiously "others" to us. The word "stranger" in the scriptures does not intend to objectify the "other" but recognizes that there are people who are indeed "strangers" to us in their culture, religion, race and other kinds of diversities that are part of the human community. Our willingness to accept others in their "otherness" is the hallmark of true hospitality. Through our openness to the "other" we may encounter God in new ways. Hospitality, thus, is both the fulfillment of the commandment to "love our neighbours as ourselves" and an opportunity to discover God anew.

37. Hospitality also pertains to how we treat each other within the Christian family; sometimes we are as much strangers to each other as we are to those outside our community. Because of the changing world context, especially increased mobility and population movements, sometimes we are the "hosts" to others, and at other times we become the "guests" receiving the hospitality of others; sometimes we receive "strangers" and at other times we become the "strangers" in the midst of others. Indeed we may need to move to an understanding of hospitality as "mutual openness" that transcends the distinctions of "hosts" and "guests".

38. Hospitality is not just an easy or simple way of relating to others. It is often not only an opportunity but also a risk. In situations of political or religious tension acts of hospitality may require great courage, especially when extended to those who deeply disagree with us or even consider us as their enemy. Further, dialogue is very difficult when there are inequalities between parties, distorted power relations or hidden agendas. One may also at times feel obliged to question the deeply held beliefs of the very people whom one has offered hospitality to or received hospitality from, and to have one's own beliefs be challenged in return.

The power of mutual transformation.

39. Christians have not only learned to co-exist with people of other religious traditions, but have also been transformed by their encounters. We have discovered unknown aspects of God's presence in the world, and uncovered neglected elements of our own Christian traditions. We have also become more conscious of the many passages in the Bible that call us to be more responsive to others.

40. Practical hospitality and a welcoming attitude to strangers create the space for mutual transformation and even reconciliation. Such reciprocity is exemplified in the story of the meeting between Abraham, the father of faith, and Melchizedek, the non-Israelite king of Salem (Gen. 14). Abraham received the blessing of Melchizedek, who is described as a priest of "God Most High". The story suggests that through this encounter Abraham's understanding of the nature of the deity who had led him and his family from Ur and Harran was renewed and expanded.

41. Mutual transformation is also seen in Luke's narrative of the encounter between Peter and Cornelius in the Acts of the Apostles. The Holy Spirit accomplished a transformation in Peter's self-understanding through his vision and subsequent interaction with Cornelius. This led him to confess that, "God shows no partiality, but in every nation anyone who fears him and does what is right is acceptable to him" (10:34-35). In this case, Cornelius the "stranger" becomes an instrument of Peter's transformation, even as Peter becomes an instrument of transformation of Cornelius and his household. While this story is not primarily about interfaith relations, it sheds light on how God can lead us beyond the confines of our self-understanding in encounter with others.

42. So one can draw consequences from these examples, and from such rich experiences in daily life, for a vision of mutual hospitality among peoples of different religious traditions. From the Christian perspective, this has much to do with our ministry of reconciliation. It presupposes both our witness to the "other" about God in Christ and our openness to allow God to speak to us through the "other". Mission when understood in this light has no room for triumphalism; it contributes to removing the causes for religious animosity and the violence that often goes with it. Hospitality requires Christians to accept others as created in the image of God, knowing that God may talk to us through others to teach and transform us, even as God may use us to transform others.

43. The biblical narrative and experiences in the ecumenical ministry show that such mutual transformation is at the heart of authentic Christian witness. Openness to the "other" can change the "other", even as it can change us. It may give others new perspectives on Christianity and on the gospel; it may also enable them to understand their own faith from new perspectives. Such openness, and the transformation that comes from it, can in turn enrich our lives in surprising ways.

VI. Salvation belongs to God

44. The religious traditions of humankind, in their great diversity, are "journeys" or "pilgrimages" towards human fulfillment in search for the truth about our existence. Even though we may be "strangers" to each other, there are moments in which our paths intersect that call for "religious hospitality". Both our personal experiences today and historical moments in the past witness to the fact that such hospitality is possible and does take place in small ways.

45. Extending such hospitality is dependant on a theology that is hospitable to the "other". Our reflections on the nature of the biblical witness to God, what we believe God to have done in Christ, and the work of the Spirit shows that at the heart of the Christian faith lies an attitude of hospitality that embraces the "other" in their otherness. It is this spirit that needs to inspire the theology of religions in a world that needs healing and reconciliation. And it is this spirit that may also bring about our solidarity with all who, irrespective of their religious beliefs, have been pushed to the margins of society.

46. We need to acknowledge that human limitations and limitations of language make it impossible for any community to have exhausted the mystery of the salvation God offers to humankind. All our theological reflections in the last analysis are limited by our own experience and cannot hope to deal with the scope of God's work of mending the world.

47. It is this humility that enables us to say that salvation belongs to God, God only. We do not possess salvation; we participate in it. We do not offer salvation; we witness to it. We do not decide who would be saved; we leave it to the providence of God. For our own salvation is an everlasting "hospitality" that God has extended to us. It is God who is the "host" of salvation. And yet, in the eschatological vision of the new heaven and the new earth, we also have the powerful symbol of God becoming both a "host" and a "guest" among us: "‘See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples...'" (Rev. 21:3).

1. For the world mission conference of 1989, cf. F.R.Wilson ed., The San Antonio Report, WCC, 1990, in particular pp.31-33. For the 1990 consultation in Baar, Switzerland, see Current Dialogue, no. 19, Jan. 1991, pp.47-51.

2. Reactions can be sent to the secretariat of the policy reference committee or to the World Council of Churches, General Secretariat, P.O. Box 2100, CH-1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland, bc@wcc-coe.org

http://www.oikoumene.org/en/resources/documents/assembly/porto-alegre-2006/3-preparatory-and-background-documents/religious-plurality-and-christian-self-understanding.html? Document date: 14.02.2006.

▶ 아래의 SNS 아이콘을 누르시면 많은 사람들이 읽을 수 있습니다.

바아르선언문 (전문)

바아르선언문 (전문)

박누가 선교사 님, 존경합니다

박누가 선교사 님, 존경합니다